For this case study, let us consider a puzzle in the Scottish landscape.

Compare these two photographs, taken in the same valley:

What do you notice about the background of these two scenes, the valley called Glen Roy?

Let’s clear away the foreground distractions and take a good look:

The U-shape of the valley is a straightforward initial observation. Many geology students will be happy to tell you that indicates this valley has been glaciated. More subtle though are the horizontal lines on the hills bracketing Glen Roy.

Take a closer look, and compare the near hill to the far hill:

These lines are perfectly horizontal, and there are three of them. In the photo below, I’m standing at the elevation of the lowest of the three, as you can see the position of the line on the near hill lines up with the position of the line on the far hill:

The elevations of these lines are at 260 m, 325 m, and 350 m:

So what do they mean? What is the origin of these features?

They’ve been dubbed “the parallel roads of Glen Roy,” but they aren’t really “roads.” One idea that might occur to your modern mind, following on from the glacial U-shape observation, is that they are glacial striations, but this doesn’t work because they don’t just go in one linear direction; instead they wrap around the landscape like contour lines on a topographic map, never deviating in their elevation. Glaciers don’t do that. Glaciers flow, and they flow downhill.

So what else is there?

Charles Darwin, that plucky young geologist freshly back from his voyage on the Beagle, took his ideas about crustal uplift and subsidence to Glen Roy in 1838. Darwin had been deeply impressed in South America by evidence of tectonic uplift: marine terraces at Coquimbo, Chile, in addition to his personal experience of an earthquake at Santiago. Of course, he had also been reading Charles Lyell, and knew that Lyell had extracted a surprising story of recent subsidence and uplift from the Temple of Serapis in Alexandria, Egypt. Lyell had used a lithograph of three columns from the temple as the frontispiece for the first several editions of Principles of Geology.

Once you learn a compelling or useful idea, it’s easy to see it everywhere. Darwin had some success by using the idea of subsidence to explain coral atolls, for instance. Now, he applied these notions of vertical motions of the crust to Glen Roy. He thought Glen Roy was a former fjord that had been uplifted, and the “parallel roads” were ancient seashores. The next year (1839), he presented this idea formally to the scientific community.

Darwin was conscious of another hypothesis, pitched in the 1810s by John MacCulloch and Thomas Dick Lauder, who suggested these were not seashores, but lakeshores. The issue Darwin had with MacCulloch and Lauder’s idea was that he could not imagine with a good way to dam Glen Roy and thus impound the water. Without a dam, there could be no lake. And with no lake, there would be no way to make a lakeshore. And Darwin knew the crust moved up and down elsewhere, so that was what he considered the best explanation for Glen Roy.

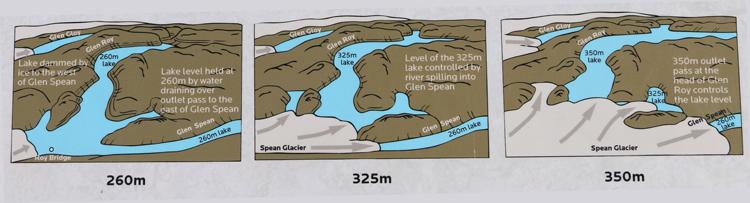

Enter Louis Agassiz, who in 1840 published Studies on Glaciers, the expression of ideas he had been promulgating since about 1837. Now there was a ready answer for the source of the requisite dam: it was made of ice! Indeed MacCulloch and Lauder had been correct, and Darwin was wrong. Glen Roy had been dammed by a glacier (the Spean Glacier), and as that glacier advanced, it blocked the flow of fresh water coming down the valley. The impounded water (a lake) found its way out of the valley at a series of three different spillways, one at 260 m (a valley east of neighboring of Glen Spean), one at 325 m (a spillway connecting an arm of Glen Roy to Glen Spean), and finally one at 350 m (the head of the Glen Roy valley itself).

So this scene…

…now looked like this in the minds of time-traveling geologic thinkers:

Here is a set of three panels from an informational sign at a Glen Roy overlook to show the sequence of events:

The “lake shore” hypothesis for explaining Glen Roy’s “parallel roads” was an important insight for later geologists examining similar features in places like Missoula, Montana. So the scientific idea was not only specifically important for this one valley in Scotland, but broadly applicable to similar situations in other locations, too – a manifestation of uniformitarianism.

The parallel roads of Glen Roy will not last forever. These subtle etchings on the hillsides are being torn down by modern fluvial erosion. The tracks of gullies and debris flows now overprint the Pleistocene glacial geomorphology, and the sharp definition of the ancient lakeshores will degrade more and more through time:

It won’t be long (a few centuries, a few millennia) before this subtle landscape signal is lost to direct observation.

Glen Roy is a terrific place to contemplate geoscience controversies in general, and an excellent place to make the point that celebrated scientists such as Charles Darwin didn’t get everything right. Darwin proposed multiple hypotheses during his career. Some of those (such as evolution by natural selection) have stood the test of time and scientific scrutiny. Others (like his “seashore” explanation for the parallel roads of Glen Roy) have been shown to be inadequate; a poor match for the available evidence. In science, we value truth above all – more than the celebrated personalities who bring that truth to light. Good ideas survive to fight another day; flawed ideas get tossed in the dustbin. Charles Darwin was not a god; he was a scientist, a generator of ideas. Some of his ideas have been validated; others discredited. This is one of the latter.

If you want to explore Glen Roy on your own from the comfort of your laptop, here are four GigaPans of the valley and its “roads.” Each can be explored with your mouse/cursor:

Further reading

“Darwin and Glen Roy.” The Darwin Correspondence Project, University of Cambridge, accessed 2020.

“Parallel Roads of Glen Roy,” Wild About Lochaber, accessed 2021.

__________________

This page was modified from a blog post by CB originally published in 2019 on the AGU Blogosphere.