After reading this chapter, students should be able to:

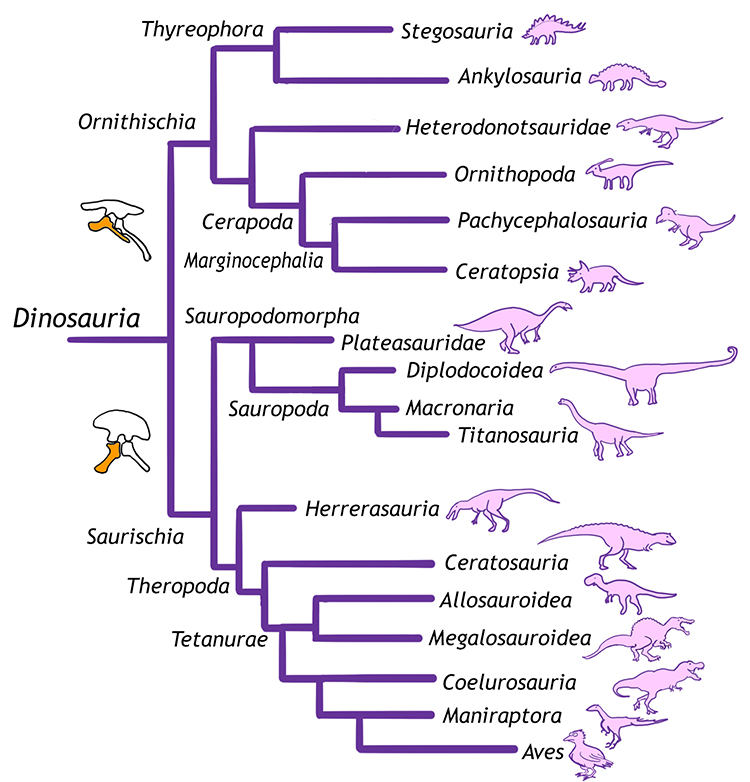

- Identify the two major groups (orders) of dinosaurs, separated based on their hips

- Describe major subdivisions within each order, like theropods, sauropodomorphs, thyreophora, ornithopods, and marginocephalia.

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles and can be classified into various different groups. Understanding these groups can not only help in placing fan favorites like Triceratops and Velociraptor into a greater context, but also to show how different animals are related to one another and evolved from common ancestors. In this case study, we will talk about the seven major groups that include the vast majority of known dinosaurs and how those groups relate to one another.

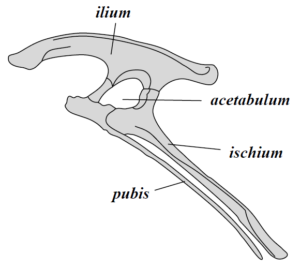

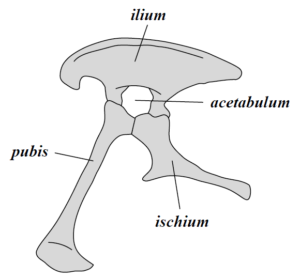

The most basic subdivision of dinosaurs is based on their hips. This division, first proposed by British paleontologist Harry Sheely in 1888, has traditionally been thought to be at the ‘order’ level in biological classification schemes, but modern research suggests that instead, it may merely be a clade. The hip has three bones: the pubis, ischium, and ilium. Some dinosaurs have a closed hip system in which the pubis and the ischium are close together. These dinosaurs are called bird-hipped dinosaurs, or Ornithischians. This style of hip is more similar to modern birds.

Other dinosaurs have an open structure to their hips with the pubis and ischium far apart and are known as Saurischian dinosaurs. Saurischian means ‘lizard hip’ because these hips are more similar to living lizards. Ironically, the dinosaurs that eventually evolved into birds are the Saurischian (lizard-hipped) dinosaurs whose descendents eventually adopted the closed-hip structure as well 一 a nice example of convergent evolution. These two branches of the dinosaur family tree are traditionally considered sister groups, but it should be noted that not all dinosaurs fall easily into one of these two groups (such as early dinosaurs like Chilesaurus and Nyasasaurus) and some paleontologists debate where to place other dinosaurs (such as the early meat-eating Herrerasaurs). Another complication is that not all scientists agree that with the premise that these are the two main groups. Most notable is a 2017 study by Baron et. al. (link to blog post) that says the traditional tree is all wrong. Since this new phylogeny is not widely accepted, below is the classic and prevailing interpretation of the members of each of the hip-based classifications.

Saurischians

Theropods

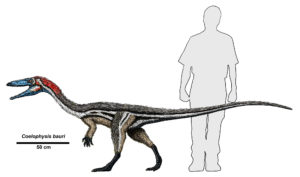

Saurischian dinosaurs have two major subdivisions: theropods and sauropodomorphs. The theropods are a diverse and complex group that are famous for meat eating. There is evidence of other dinosaurs being omnivores, and there are some theropods that strayed from a carnivorous diet, but all of the famous dinosaurs with big sharp teeth are theropods. Early (basal) theropods were swift and small like Coelophysis. Its name, which means ‘hollow form’, is a reference to an important trait that all theropods share: hollow bones. This made them lightweight, and therefore presumably more agile, which is helpful in chasing down prey. A less obvious but related trait they share is a series of air sacs used throughout the body used in respiration, at least partially filling the empty spaces in bones. This mechanism, seen in their living descendents today (birds), also helped allow a high level of activity while releasing heat more efficiently. Their other most notable shared trait is the three-toed feet with sharp claws.

Evolutionarily, the theropods trended larger over time, a development first seen in Dilophosaurus. Contrary to its petite portrayal in the Jurassic Park movie franchise, it was over 20 feet long. As features such as a neck frill and the ability to spit poison are difficult to preserve in the fossil record, there is no direct scientific evidence for either. By the end of the Jurassic, these early large theropods diversified into famous forms like Ceratosaurus.

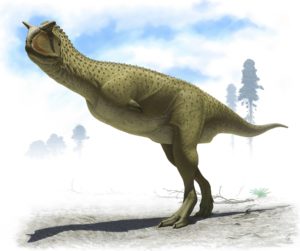

Ceratosaurs would become truly massive in the Cretaceous, especially in South America, which was an isolated continent at the time. This is most exemplified by Carnotaurus, a name that means “the meat-eating bull,” which had incredibly small vestigial arms. A sister group to the ceratosaurs, Tetanurae, was a more advanced branch of the theropod tree. This would have several branches, including the allosaurs (Allosauroidea), which lead to animals like Allosaurus, and the megalosaurs (Megalosauroidea), which had the crocodilian-like spinosaurs and the first dinosaur ever scientifically described, Megalosaurus. Interestingly, the allosaurs also got large and fierce in South America, with animals like Carcodontosaurus and Giganotosaurus, which were both estimated to be up to 40 feet long. These are arguably the largest land-dwelling theropods ever.

The third branch off Tetanurae is Coelurosauria. This group is best known for the evolution of feathers. While skin and related features are rare to preserve, there is significant evidence that scientists have been able to estimate that all members of this group had some form of feathers. Some of the larger members may have shed them with age (like the birds do with down that keeps them warm as juveniles) or evolved them away, but those details are difficult to discern from the fossil record. Most of the largest members of the group, where skin impressions have been found, show no feathers at all. This was complicated in 2012 when Yutyrannus (meaning ‘feathered tyrant’) was described. It was clearly a coelurosaurian, and an early tyrannosaur, but was almost 30 feet long and covered in early feather-like structures.

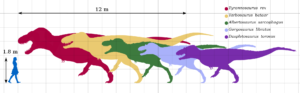

The earliest group of the coelurosaurians are the tyrannosaurs. Starting out small in the Jurassic, with many early members smaller than a full-grown human, their descendents became massive by the late Cretaceous. Famous examples include Daspletosaurus, Albertosaurus, Tarbosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus. All of the large members of the family had short arms with two digits, though evidence suggests that the arms still had some function. What that function is conjures much debate, from predation to mating. The group appears to have evolved in Asia, and although many of the larger, later members are famous from western North America, they also lived in Asia, on the east coast of the United States, and possibly even Australia.

Heading along the coelurosaur family tree, the next major group is Compsognathus and relatives, which were very small and delicate and probably ate insects and small animals like early mammals and lizards. Next are the ornithomimosaurs, whose name means “bird mimic lizards.” These dinosaurs had a body plan similar to ostriches, including a toothless beak. No teeth means a meat-eating diet is not an option, so these animals were mainly herbivores. They were only moderately sized, with the exception of Deinocherius, who was truly strange! It was 35 feet long, including a 3.5 foot long head with a duck-like bill, and the tail vertebrae which implies tailfeathers. It also had 8 foot long arms (the longest of any theropod) with giant claws and a sail on its back.

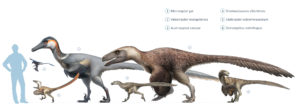

A sister group to the ornithomimosaurs is the maniraptorans, or ‘thief hands.’ They have several adaptations that make them more bird-like, including the wishbone, which only they have. Dinosaur groups within Maniraptora include the short-armed, one-fingered alverezsaurs, the therizinosaurs who had the longest claws in the history of life (at over 3 feet), the poorly named (not egg eating or stealing but brooding) oviraptors, and the group paraves, which means ‘next to birds.’ Subdivisions of Paraves include Eumaniraptora and Deinonychosauria.

Within Paraves, the most notable dinosaur group is the dromaeosaurs, colloquially known as the raptors. The trait that most identifies them is their second toe sickle claw, which was held above the ground. Velociraptor is perhaps the most famous member of the group due to the Jurassic Park films, but the animal in the movie is actually patterned after Deinonychus, a larger raptor. In fact, the animal that most matched the movie depiction is Utahraptor, which ironically was published and named just days after the film’s premiere. Deinonychus is also important because when it was described in 1969 by Jon Ostrum and Robert Bakker, it helped spark the Dinosaur Renaissance, which led to our modern ideas of dinosaurs as dynamic animals instead of the lumbering beasts of the early 20th Century.

Video by PBS that breaks down how dinosaurs are related to birds.

A related group to the dromaeosaurs is avialae, which can be considered (depending on definitions) to be birds. It is assumed that all members of this group were capable of powered flight. Archaeopteryx, traditionally known as the first bird, would be an early member of this group. This group originated in the Jurassic and became quite prolific in the Cretaceous, and led to the group Neornithies, which is the clade that includes all modern birds. Current analyses consider the ratites, the group which includes large flightless birds like ostriches and emus, to be the most primitive in the modern bird phylogeny.

Theropods: Did I Get It?

Sauropods

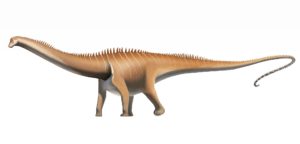

The other group of saurischian dinosaurs, the sauropods, are thankfully much less complicated than the theropods. Sauropods became the largest animals to ever walk the earth, but they started out relatively small like other dinosaurs. Early sauropods were traditionally called prosauropods, but that term has started to become unpopular. The preferred term, to encapsulate the entire sauropod clade (all true sauropods and their ancestors) is sauropodomorphs. Early sauropodomorphs (now called Plateosauridae) were bipedal and probably omnivores, with sharp claws on their hands that could have helped tearing vegetation or flesh. The best example of an early sauropodomorph is Plateosaurus. It had blunt teeth and was about twice as tall as a human. It also had an elongated neck, allowing it to reach leaves that most other species at the time could not access.

Over time, the sauropodomorphs got larger and larger. The important step from early sauropodomorphs to true sauropods is when their weight became so large that they were permanent quadrupeds. There is debate as to which genus represents this transition, but an animal like Melanorosaurus or Vulcanodon are good candidates. It has more robust limbs, with specifically longer hind limbs with less-useful claws, to support its increasing weight. Interestingly, the teeth of these animals were not what you would expect for a tree browser. They kept their omnivore-like needle teeth and used gastroliths, small rocks they would swallow and store in their gizzards to help digest the tough plant material, instead of grinding and chewing their food in their mouths.

Early sauropods include the club-tailed Shunosaurus and the incredibly-long-necked Mamenchisaurus. All sauropods still have a front toe claw, a legacy of their bipedal beginnings. More derived sauropods split into two major groups: The first group are the diplodocids (Diplodocidea), which had a long body plan. This group includes Apatosaurus/Brontosaurus (which may be the same animal or may be different animals depending on who you ask), the spiny-necked dicraeosaurs, and the namesake of the group, Diplodocus.

The other major group of sauropods is Macronaria. These are animals that had a more upright stature, most famously demonstrated by Brachiosaurus. A subgroup of macronaria are the titanosaurs. As the name suggests, these were generally very large animals that commonly had some armored skin coverings made from bone. Included in this subgroup is Argentinosaurus, which is the best candidate for the largest known dinosaur, based on decent fossil remains of a leg and spine. Upper estimates for its size is 130 feet long and 100 tonnes. Other titanosaurs, such as Sauroposeiden and Patagotitan, may be larger but are estimated from more incomplete remains.

Sauropods: Did I Get It?

Ornithischians

The sister group to saurischia, the ornithischians are a diverse group of dinosaurs. Their hip, which is more flattened and pointed towards the tail, allows for a larger gastro-intestinal system which these animals used to process their almost exclusively plant-based diets. The first ornithischians were small bipedal runners, with Lesothosaurus claiming the title of oldest ornithischian and the Heterodontosaurs being the most famous members of this group. Like the name implies (hetero=different, dont=tooth, saurus=lizard), these animals had a unique trait that most reptiles do not, neither at that time nor even today: differentiated, specialized teeth. They had more rasping teeth toward the back of their mouths and more spiky teeth toward the front. They also had an extension of their jaw in front of the teeth. This would become a beak in its descendents, a feature that is common in many ornithischians.

Thyreophora

Stegosaurs

There are two major subgroups within ornithischia: thyreophora and neornithischia. Thyreophora represent the group of armored dinosaurs, which had bony buildups protruding and covering the skin. The stegosaurs, one major branch of the thyreophora tree, were common in the Jurassic. Their bony plates on their back are still one of the biggest mysteries in paleontology. Various ideas, from thermoregulation, defense, and sexual display have been proposed, but none have been fully convincing. One thing to consider is related animals, like Kentrosaurus and Miragaia, had very different set ups. Any explanation of why Stegosaurus’ had its plates has to explain why others did not have them.

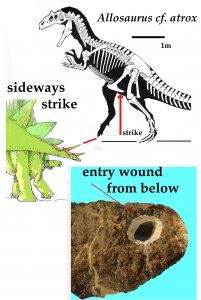

Less confusing are the defensive tail spikes, which match holes in the bones of predatory dinosaurs at the time. Jokingly called a ‘thagomizer’ in a Far Side cartoon by Gary Larson in the 1980s, this name has now been somewhat accepted in the scientific community. One famous example of the thagomizer’s impact was first presented in 2014 by Robert Bakker and colleagues in which an Allosaurus had a hole in its groin that abscessed and probably killed the animal. The most likely cause of the hole is a thagomizer spike.

Ankylosaurs

The other major group of thyreophorans are the ankylosaurs (Ankylosauria). These were heavily armored tank-like animals common in the Cretaceous. There are at least two major subdivisions in this category: the tail-clubbed Ankylosauridae and the more spiky Nodosauridae. Common depictions of Ankylosaurus, as in the Jurassic World films, show an unrealistic hybrid that had the shoulder spikes with the tail club, but in reality it was one or the other.

Early Ornithischians and Thyreophora: Did I Get It?

Ornithopods

The other side of the ornithischian tree (i.e., Cerapoda/Neornithischia) has three other major groups. The more complex, diverse, and prolific of the three are the ornithopods. Their name means ‘bird feet’ due to the three toes, but remember that the theropods (only distantly related) were the group that evolved into birds. Their success did not come from armor, speed, or size but something much more mundane: chewing. Their tooth battery would remind one of a modern horse or cow; highly complex (for the time) and effective at breaking down tough plants. Like other groups, they started small and bipedal (like the hypsilophodonts), but eventually grew larger. The large ornithopods are speculated to be somewhere between a biped and a quadruped like a chimpanzee or gorilla. A famous member of this group that is transitional between the early and later ornithopods is Iguanodon. Though quite large, its thumb spike and prehensile pinky must have had some purpose, suggesting it had to spend some time on two legs.

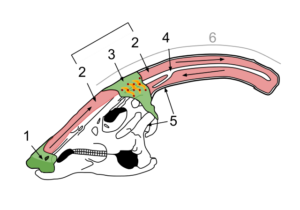

When the average person thinks of the animals in this category, typically the word they would use to describe them would be ‘hadrosaur’ or ‘duck-billed dinosaur.’ These terms are appropriate, but only for the more derived members of the group. So while Iguanodon is not a hadrosaur, other famous ornithopods like Parasaurolophus and Edmontosaurus are hadrosaurs. The hadrosaurs break into two major groups: the saurolophines (formerly known as hadrosaurine) which had no crest or solid crests and the lambeosaurines which had hollow crests. One famous member of saurolophines is Maiasaura, the first dinosaur found with definitive evidence of parenting, hence the name, ‘good mother lizard.’ The young of Maiasaura were found to have worn teeth before they had the ability to walk, suggesting the mother had to have brought food to the brood. Parasaurolophus is a famous member of the lambeosaurines. Their hollow crests have been speculated to allow them to make sounds, presumably to communicate with members of their own species.

Ceratopsians

The sister group to the ornithopods is marginocephalia. These animals also had tooth batteries, but also had head ornamentation. Marginocephalia has two major subdivisions. The first is the ceratopsians, or horn-faced dinosaurs. It should be noted that despite the name, not every member of this group had a horn on their face. What was much more universal was a frill, a bony projection that extended from the skull back towards the neck. Early members of the group were from Asia and were small with tiny frills. A famous early example is Protoceratops from Mongolia. The name, which means ‘before horned face’, shows it had the neck frill and just the smallest bumps where horns evolved in others.

Within the ceratopsian family, there are two subfamilies. The chasmosaurs typically had more trapezoidal frills with larger brow horns. The most famous member of this group is Triceratops. The centrosaurs typically had larger nose buildups (horns and sometimes bulbous bony growths) and spikes on the frill. Styracosaurus is a famous example of a centrosaur. There is still much debate as to the purpose of the horns, spikes, and frills. Popular convention interprets these items as defenses from predators. While there is some evidence for this, not all scientists agree that they were defensive, especially the frills. Most ceratopsians’ frills were weak and thin, especially in the centers of each half, making them useless against direct combat. Other ideas for their growth include sexual display and species recognition. This goes along with many fossil deposits of ceratopsians that show many individuals in the same place of different ages, which suggests herding or other social behavior.

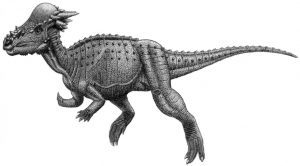

Pachycephalosaurs

The other branch of marginocephalia is the pachycephalosaurs, a name that means ‘thick headed lizards.’ They were bipedal and smaller than many other dinosaur types, with the largest animals just reaching the height of a grown human. Their head buildups did not result in frills or true horns, but a dome head surrounded by small spikes. This dome is often suggested to be for intra-species combat over mates or territory, similar to what rams or deer do today. The evidence of this, like so many other things in the fossil record, is circumstantial and incomplete. Their domes could have been used for similar things as their ceratopsian cousins: mating and recognition. Another complication scientists have between the pachycephalosaurs is naming and differentiating them. It has been proposed that many individual genera may be invalid, with these variations proposed to instead reflect differences in age or gender. Stigymoloch and Dracorex, for example, have been proposed as the subadult and juvenile versions of Pachycephalosaurus, respectively.

Cerapoda: Did I Get It?

Final Thoughts

Obviously, there is still much to learn about the dinosaur family tree, in how individual members are placed and how they are interrelated. Understanding the seven major groups, theropods, sauropods, stegosaurs, ankylosaurs, ornithopods, ceratopsians, and pachycephalosaurs, is a first step to help the novice place a new dinosaur in the greater context, and also understand the history of life a little bit better. As more discoveries are presented, old ideas have been abandoned in favor of better hypotheses, with inconsistencies and unknowns debated, both hallmarks of science. How these animals fit into the greater reptile family tree in the Mesozoic also demonstrates these changing ideas of evolutionary history, as well as great examples of convergent evolution. Even our understanding of modern animals, like birds and crocodiles, has been enhanced as we learn about their extinct dinosaur relatives. For more details on the debates within the dinosaur family tree, please read the dinosaur debate section of this text.

Further Reading

Bakker, R. T., Zoehfeld, K. W., & Mossbrucker, M. T. (2014, October). Stegosaurian Martial Arts: A Jurassic Carnivore Stabbed by a Tail Spike, Evidence for Dynamic Interactions between a Live Herbivore and a Live Predator. In Gelogical Society of America (GSA) Annual Meeting. https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2014AM/webprogram/Paper247355.html

Baron, Matthew G.; Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul (2017). “A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution” (PDF). Nature. 543 (7646): 501–506.

Brusatte, S. The Rise and Fall of Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World